The children of Mars are depicted here very negatively they are murderers and thieves, hot-tempered and angry. In pictures they are then also always represented in the war or with robbing, plundering, murdering or in the deadly duel. The attribution of Mars with war is clearly shown here. But we do not find the Fechtkunst(art of fencing) here. Neither in word nor in picture.

On the contrary, the children of the sun.

Sol die Sun man mich heissen sol

Der mittelst planet pin ich wol

Warm vnd trucken kan ich sein

Naturlich ganntz mit meinem schein

Der lew hat meins hauß kreiß

Dor inn pin ich vast heiß

Doch ist Saturnus stetiglich

Mit seiner kelt wider mich

Erhohet werd ich in dem wider

In der maget falle ich herwider

In dreyhundert vnd funffundsechtzig tagen

Mag ich mich durch die zeichen tragen.

Ich pin glucklich edel vnd fein

Also sint auch die kinder mein

Gele weißgemengt schon angesicht

Wolgebartt weiß clein hare geslicht

Ein feisten leip mit scharpffen hirn

Mittel augen ein grosse stirn

Seitenspil vnd singen von mund

Wol esszen vnd grosser herren kunt

Vor mittem tag dienent sie got vil

Dar nach leben sie wie man wil

Steinstossen schirmen ringen

In gewalt sie gluckes vill gewynnen.

(Germanisches Nationalmuseum: Mittelalterliches Hausbuch Bilderhandschrift des 15. Jahrhunderts, Leipzig 1866, S. 7)

The children of Sun are noble, fine, happy and intelligent ("scharrpfen hirn")(intelligent). They are the opposite of the children of Mars. Instead of waging war, they pursue the fine things in life, such as music, stone-pushing, schirmen(old word for defensively fencing) and Ringen(wrestling). And it is pointed out that these also help in case of threats of violence, that is, they are protectors. The fact that Schirmen and Ringen are mentioned here as part of the Fechtkunst(art of fencing) will also be important later.

In any case, it is shown here that the attributes of Mars are evaluated very negatively. The art of fencing and wrestling on the other hand, here as Schirmen and Ringen, is shown as something positive for body and soul, that one exercises as "Kurzweil" thus hobby or fun but nevertheless in the seriousness is helpful. But it is not attributed to Mars but to the sun.

But even the German word Kampf can hardly be associated with ars martialis here. Kampf and Kämpfen clearly appear in the medieval language only in connection with earnest confrontations. As a rule, however, as a word for Zweikampf or Duell(duel). Thus, a Kämpfer(combatant) is in turn a participant in Kampf(combat) and is also called a Kämpfer(combatant). The Latin translation in medieval texts is pugil, pugillator, pugnator, duellator for Kämpfer, duellare, pugillare, as well as pugnare for the verb to kämpfen(fight) and duellum for Kampf(combat).

This is exactly how the terms are found in the legal texts of the High and Late Middle Ages, from the Sachsenspiegel to the Land Laws and City Laws. Kampf can mean both the judicial duel and the honor combat.

The connection to Zweikampf(duel( thus becomes very clear. The word Kampf(combat) is then also found in the fencing books of the 14th and 15th centuries. Thereby the Kampfs is subordinated to the term fencing and also always declared in the context of duel. In the courtly Liechtenauer teachings of the 15th century, the word Kampf is always found in the context of the knightly honor duel in armor on horseback or on foot.

...das ist der text vnd die glos einer gemainen ler zw kampff...

(Rom, Biblioteca dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana, Cod. 44 A 8 [Cod. 1449] fol. 53 v.)

Das ist der text vnd die glos von Ringen zw kampf...

(Rom, Biblioteca dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana, Cod. 44 A 8 [Cod. 1449] fol. 56 r.)

Hie hebt sich an meister lewen

kunst fechtens In harnasch auß

den vier hutten zu fus vnd zu

kampffe etc.

(Augsburg, Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg, Cod. I 6 4o 3, fol. 54 r.)

hie vint man geschriben von dem kempfen

Item wie daz nun sy daz die die

decretaleß kempf verbieten, So hat doch die gewonhait herbracht von

kaisern und künigen fürsten und hern noch gestatten und kempfen laussen,

und darzu glichen schierm gebent, und besunder und umb ettliche sachn

und artikeln, alß her nach geschriben staht. Item

zu dem ersten maul daz im nymant gern sin Eer laut abschniden mit

wortten ainem der sin genoß ist Er wolte Er hebat mit im kempfen wie wol

er doch nit recht wol von im kem ob er wolte und darumb so ist kämpfen

ain muotwill... (Kopenhagen, Kongelige Bibliotek, Thott 290 2o fol. 8 r. f.)

Especially in the last quotation by Hans Talhoffer from the time around 1459, it becomes clear that dueling was a battleground between ecclesiastical and secular spheres at that time. He distinguishes between honorary duels ("Eer abschniden", "muotwill") and then shows the criminal charges from which judicial duels could be fought. The subject of judicial duels is so extensive that I do not want to elaborate on it here. In any case the text following the quotation in the source corresponds to the formulations in the land laws of Bavaria, Franconia and Swabia. Kampf(combat) therefore clearly means duel in its various forms. And above mentioned Latin terms are used in Latin text versions for Kampf, Kampfer and Kämpfen.

Fechten(fencing) describes, on the one hand, the activity of physical combat as a whole and the activities that one learns in order to succeed in combat. However, in the Middle Ages Fechten was mainly practiced for amusement, i.e. for the purpose of physical and mental fitness, i.e. as a hobby. However, it is always mentioned that this also prepares one well for possible violent situations. Only a select group of people also learn pieces that are explicitly intended for serious situations and Kampf(combat). Special mention is made of Fechten in the Hofkünste(courtly arts), which are part of the noble-knightly training and, from the 15th century, become increasingly accessible to the urban patrician class. Thus, for example, sons of patricians are educated and trained at noble courts.

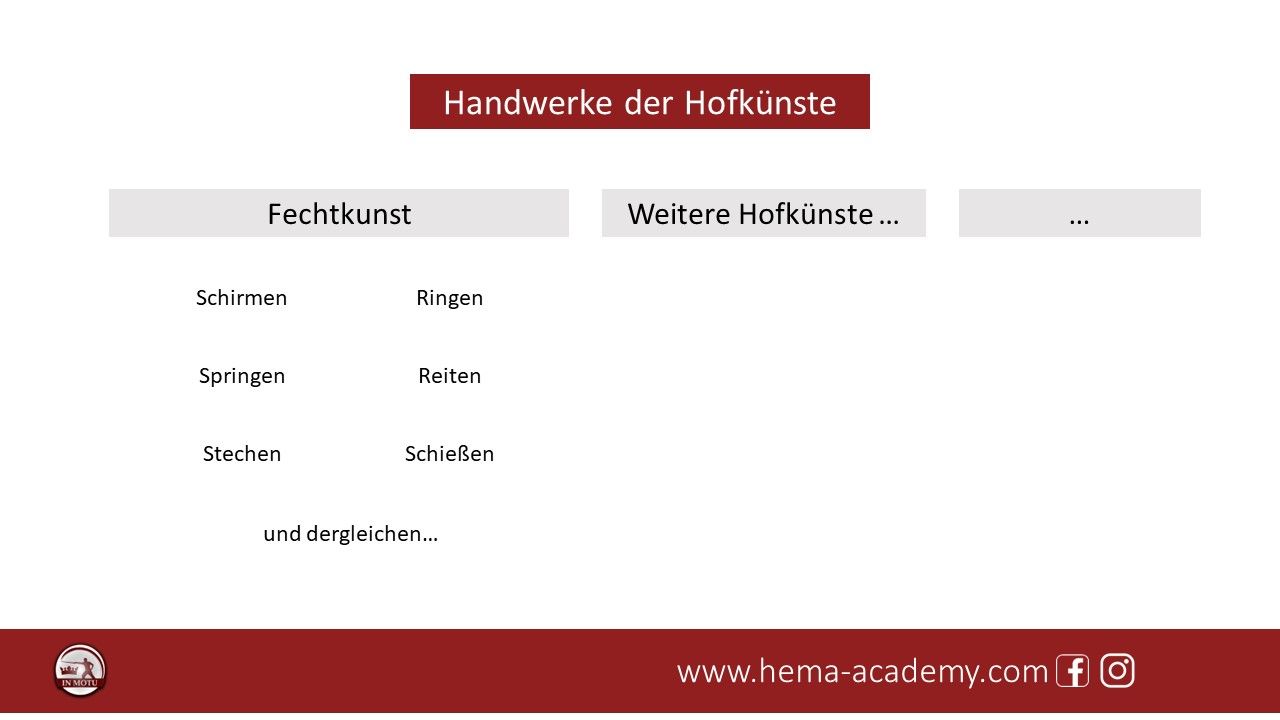

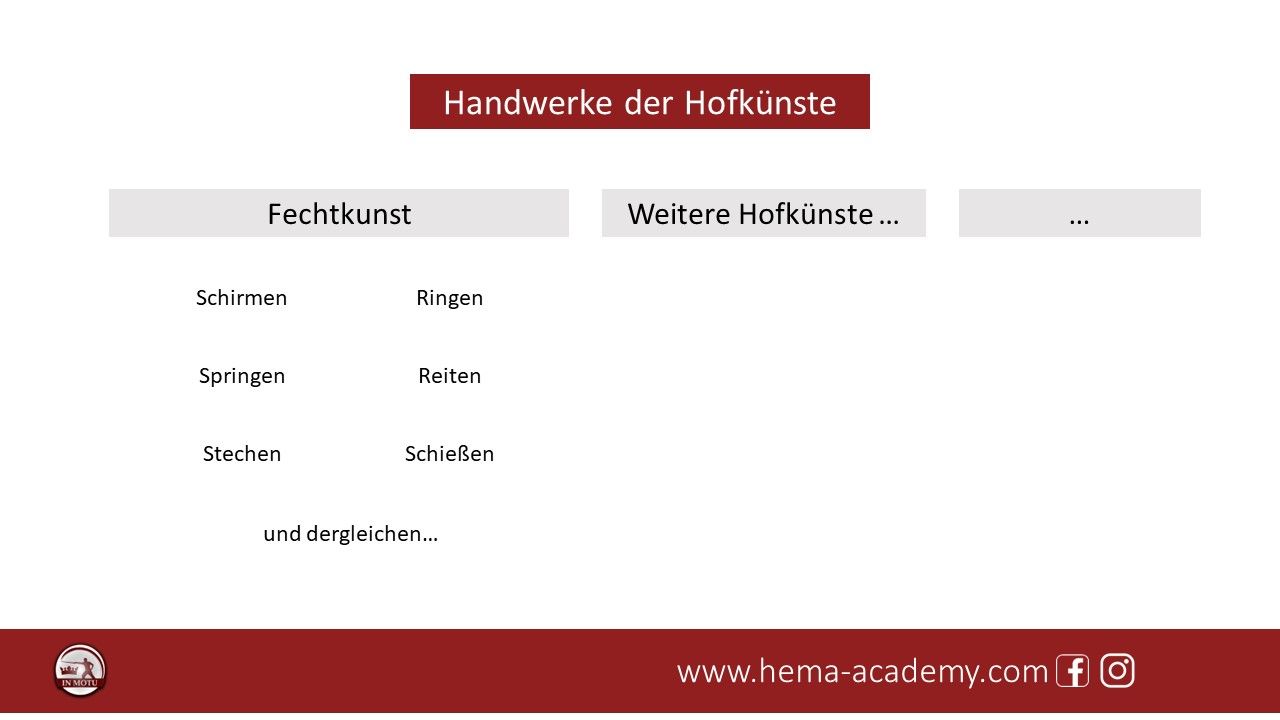

Fechten is the generic term and is divided into Schirmen (fencing with (hand)weapons), Ringen (fencing with the body), Reiten(riding), Stechen(kind of jousting), Springen(jumping), Schießen(shooting) and similar "Handwerke"(crafts).

In Latin, fencing is always translated as dimicare. And the art of fencing is the ars dimicandi (and other spellings). Already the oldest fencing book MS I.33, which was probably written around 1300, calls the art by this name. And the root of the word dimic(are) can be traced back to antiquity.

It can therefore be strongly assumed that ars dimicandi and Fechtkunst or die Kunst des Fechtenst(he art of fencing) in the German-speaking world are the oldest terms that can be found for what we call Kampfkunst(martial arts) or Kampfsport(combat sports) today. For Fechtkunst as a generic term for all kinds of fencing and gymnastics from wrestling, boxing, "Gerätfechten" to rifle fencing can still be found in the 19th and 20th centuries, while the terms Kampfkunst, Kampfsport and martial arts only spread in the second half of the 20th century. Even today, for example, in the German Armed Forces it is still called Gefecht and there are commands like "Klar zum Gefecht!" and not "Kampf!" or "Klar zum Kampf!".

Also in the course of the "rediscovery of antiquity" (Renaissance), which began in the Middle Ages, one could now think that possible word creations arose via the new strengthening of Latin. However, even in the Latin works of a Henrich von Gunterrodt and his references to wrestling, boxing and pankration in antiquity, there is no reference to ars martialis, so that one must assume that this word was not used in antiquity, the Middle Ages or the early modern period. Gunterrodt also calls the art ars dimicatoria.

Further research here would have to intensify on the 20th century, since we are probably dealing with a neologism that may be traceable to the increasing international linguistic dominance of English after World War II and then wrongly projected back to past eras.

For example, one theory could be that the international spread of Asian-influenced "martial arts films" since the 1960s are the starting point for the words we use today in the first place. Starting with the international language English, Martial Arts was probably introduced to the film industry, possibly driven by the Asians themselves, who were looking for an English word to describe their arts. From English it was then translated into the other languages. How one came however from martial arts to Kampfkunst, is further a mystery to me, one would have to translate it nevertheless correctly with Kriegskunst(art of war), if one would like to follow the ideas of the "experts" mentioned at the beginning.

Einen kurzen Ausblick möchte ich noch auf andere europäische Sprachen geben. Denn auch in Italien, Frankreich, den Beneluxstaaten, Dänemark und Skandinavien scheinen die deutschen Begrifflichkeiten den Ursprung für Fechten und teilweise auch Kämpfen zu bilden. Gerade das deutsche Schirmen findet sich im Französischen (

l' escrime), Italienischen (

scherma) und Spanischen (

Esgrima) schon vom Mittelalter bis heute. Im Englischen ist es ebenso interessant, das das englische to fight aus dem einstigen Wortstamm fechten näher an Kämpfen ist und es ein eigenes Wort

fencing gibt, was das meint, was im Mittelhochdeutschen mit

Schirmen bezeichnete wurde, nämlich das Fechten mit Handwaffen ("

fighting with..").

Fechten/Schirmen

Latein - dimicare (Verb)

Französisch - escrime

Spanisch - esgrima

Italienisch - scherma

Niederländisch - schermen

Dänisch - fægte

Englisch - fencing (correctly in the middle ages Fechten=fighting and Schirmen=fencing)

Kämpfen

Latein - pugnare (Verb) duellare (Verb)

Französisch - combat

Spanisch - combate(s)

Italienisch - combattimento

Niederländisch - vechten, strijden, worstelingen

Dänisch - kampen

Englisch - fighting/combat

Krieg

Latein - bellum

Französisch - guerre

Spanisch - guerra

Italienisch - guerra

Niederländisch - strijd

Dänisch - krig

Englisch - war

It would be very interesting for my research to compare the medieval ways of speaking in relation to Latin using contemporary sources, since modern Latin translators are already modern interpretations without historical reference.

As an example, consider the term Ritter. In medieval Latin texts, the Latin miles is used for Ritter(knight) in Europe. This is equated in French with chevalier in Italian with cavaliere, in Spanish with caballero and in English with knight.

If you enter miles in a modern dictionary and compare it to the languages mentioned, you will find soldat in French, soldato in Italian, soldado in Spanish and soldier in English.

I think it shows well from a historical point of view that in Central and Western Europe they had a very uniform, clear way of speaking about Kämpfen(fighting), Fechten(fencing) and Kriegsführung(warfare) and actually still would have today.

The myth of the Ars Martialis and Martial Arts is probably due to Hollywood and the desire to generate more action by creating a martial connection. It may be the American influence on European linguistic culture that created new terminology here. It has blurred our linguistic roots in this area.

In his book "The Invention of Martial Arts: Popular Culture Between Asia and America", Paul Bowmann discusses precisely this linguistic and cultural development several times. He shows that the term martial arts emerged from this Asian-American exchange and that its origin was only to designate the Asian martial arts. He explicitly refers to 3 first works that begin this word creation in 1920, 1933 and 1955. The actual boom of this new word martial arts is to be set between 1968 and 1974, i.e. the start of the "martial arts films" in the USA, which are strongly influenced by the Asian arts.

The term martial arts is therefore neither ancient, nor medieval, nor Western. It was created to give a name to the Asian fighting arts so that they could be distinguished from the existing ones. The boom of this term, however, has "unfortunately" led to the actual western terms being overlaid by this new term in only a few generations.

I find the connection to martial in relation to European arts very questionable in several respects. Firstly, as a historian and teacher of historical fencing arts, I see the problem that we are hindering intellectual access to the historical sources and the thinking of contemporaries. The sources work with the European generic terms, many of which had survived into the 20th century.

Furthermore, the martial term is questionable because the connection to an alleged martial background of the arts is simply wrong. And it is quite significant when precisely the "children of Mars" are devalued by contemporary people in the Renaissance of the 15th-16th centuries. Martial not only implies a false image of the arts, which originally and causally until the 20th century served primarily to strengthen the mind and body, i.e. hobby, fun and further development, but often also forms a correspondingly martial ethos. So much so that some even appropriate the word warrior, which has no connection whatsoever. However, anyone who examines the ethos of the arts of fencing since the Middle Ages in a linguistically correct manner will only come to the realisation that these arts always imply an avoidance of unnecessary violence and that the use of violence is always a last resort when others have failed, as in the case of some duels.

As a small summary

Krieg(war) is

bellum.

Kriegsführung(warfare) is militaris.

Die Kunst der Kriegstechnik(the art of war engineering) is ars belli or armatura.

Die Ritterkunst (the knightly art) is ars militaris.

Der Ritter (Krieger)(knight/warrior) is miles.

Die Fechtkunst(art if fencing) is ars dimicatoria.

Der Kampf(combat/duel) is duellum or pugnam

More importantly, however, we need to use this knowledge in research around the Fechtkunst (art of fencing). Because for the exchange a uniform technical language is necessary and that the current technical language moves around the terms Kampfkunst(martial art), Kampfsport(combat sport), complicates immensely the access, the understanding and the exchange around the historical arts. Because if the same words have different meanings today and back then, then we have to think about how we want to shape the exchange linguistically.

It starts with the term HEMA (Historical European Martial Arts), which has no relation to the original language. Because in English it should correctly be called HEFA (Historical European Fighting Arts). And in German it would be Historische Europäische Fechtkünste.

In any case, the connection of the Fechtkünste(fencing arts) with the Kriegskünste (arts of war) can hardly be established. In essence, fencing is not "martial" or warlike, but rather a cultural enrichment, which even then was considered in its main focus as a diverse and extensive method to develop body and mind in many ways. The preparation for actual possible acts of violence was not in the foreground. But it was clear to the people that the fencing arts were nevertheless at any time a good condition to defend oneself in any form.

I hope to be able to stimulate fruitful thoughts with this.